This is a difficult subject to treat because I myself am reaching the age at which one can pay most grievously for mistakes made earlier in life. I have just finished re-reading Joseph Conrad’s The End of the Tether, about a British sea captain in Malayan waters who has passed up a peaceful retirement to help out his daughter, who had married unwisely.

Although Captain Whalley in his youth was one of the most brilliant sea captains in the South Seas, he has grown old and forced himself to take on a rickety steamship in need of repair. The owner is a nervous former lottery winner who serves as the ship’s engineer. While he spends every spare hour evaluating possible winning lottery numbers, Captain Whalley, with the help of a native serang, handles the sailing of the vessel.

Unknown at the outset is that Captain Whalley is going blind, and it is primarily the Malay serang who is responsible for captaining the ship. As one can guess, things do not end well.

As I approach eighty years of life on earth, I see many of my friends in their retirement years similarly afflicted as a result of difficult situations that over time have gone critical. I earnestly hope that I will not be one of them.

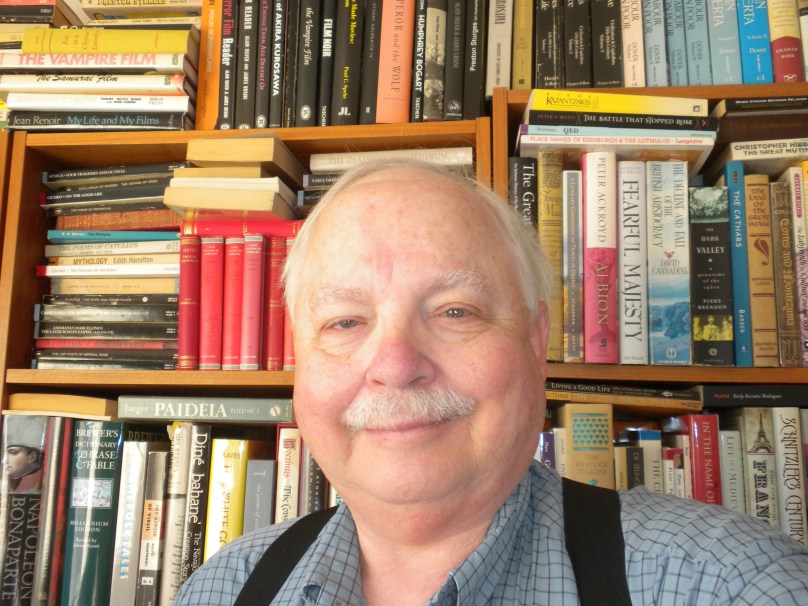

For one thing, I did not save up enough money for retirement, having spent obscene amounts of money on books. Today I have a fantastic library of five or six thousand volumes. But what happens if I should suddenly die? That would leave Martine in the position of trying to find out how to turn my library into cash, if possible. This at a time when there are precious few bookstores around that could buy hundreds of books at a time.

At least I don’t buy books any more. The Los Angeles Library and my Amazon Kindle account for most of the books I read.

I owe it to the people I love to whittle away at my library, however it pains me. Alas, I am mortal. I have made mistakes. I will pay for those mistakes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.