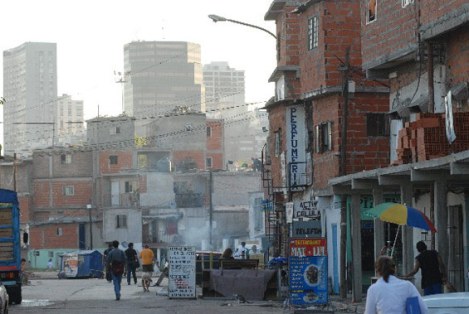

The New World gave the European conquerors many gifts, including potatoes, tomatoes, chocolate, tobacco, corn, vanilla, chili peppers, bell peppers, pumpkins, avocados, peanuts, cashews, pecans, quinine, wild rice, quinine, squash, and many types of beans. They were richly rewarded with such European gifts as measles, smallpox, and malaria. The mortality rate in Mexico alone was in the millions in the 16th century alone.

Most people do not realize that the malaria mosquito was a stowaway on ships that brought slaves from Africa. Mayan records make no reference to malaria, and many jungle areas in Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico were inhabited which over the last several hundred years have been abandoned. The Petén region of Guatemala has hundreds of Mayan archeological sites, and more are being discovered each year. Where Mayan cities used to be connected by sacbés, or ceremonial roads, today they are connected by shoulder-deep mud. Much of the Yucatán Peninsula is now sparsely populated thanks to the devastation wrought by the malaria mosquito.

According to the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement in France:

A large international study recently published in the PNAS by scientists from the UMR Migevec and their partners has shown that P[lasmodium] falciparum crossed the ocean on slave ships which crossed the Atlantic between the 16th and the 19th century, some 500 to 200 years ago. The research team has indeed just demonstrated that the parasite which is now found in America has African origins.

Through a global international scientific collaboration, biologists have collected several hundred samples of infected human blood from 17 countries representing the parasite’s entire distribution area. It is one of the largest sets of P. falciparum genetic data ever collected. The analysis of genetic material extracted from those samples has taught the scientists several things. First of all, the American pathogen is genetically distant from its Asian cousin, thus precluding an Asian origin. It is, however, close to the African parasite.

The IRD further concludes that the culprit were slaves who were brought into the Spanish and Portuguese colonies, partly, ironically, because blacks were more resistant to malaria.

When I go to Guatemala and Honduras later this year, I will spend part of the time in malarial jungles, which means I will be taking chloroquine and traveling with a mosquito net to place over my bed.

I hate mosquitoes, but I would dearly love to see the Mayan ruins, which are now in areas that are sparsely developed. The city of Tikal once had a population of 300,000 during Europe’s Dark Ages. Today, the entire Petén Department has a population under 700,000, mostly around La Libertad, San Luis, and Sayaxché.

You must be logged in to post a comment.