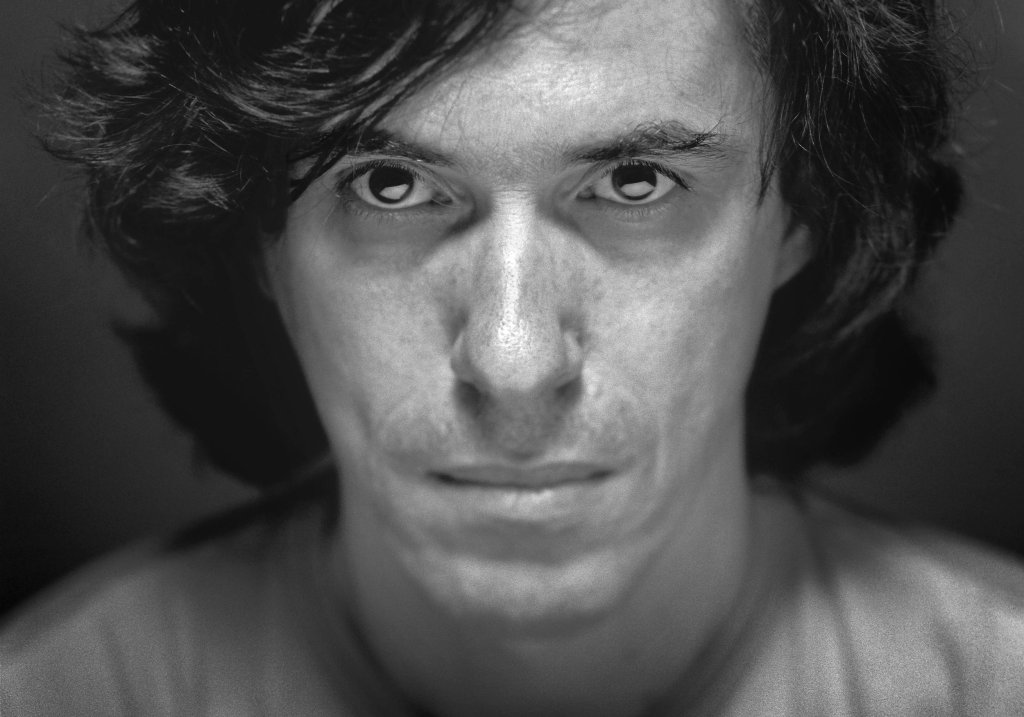

Romanian Writer Mircea Cărtărescu

For their reading, Americans tend not to look beyond English-speaking North America and the countries of Western Europe. As a Hungarian, I have always delighted in the literature of Eastern Europe. In this post, I will give you a list of some of my favorite recent fiction from the former Soviet satellites, including one Ukrainian author, because Vladimir Putin is trying to turn his country into a Russian satellite.

I do not include any Russian authors—not because of any prejudice against—but because the field is so rich it deserves a separate post. Here’s the list in alphabetical order by author:

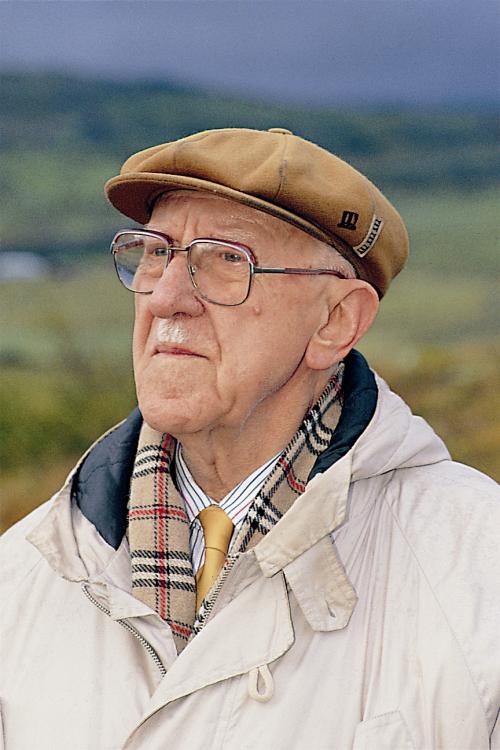

Ivo Andrić (Bosnian 1892-1975)

Won the Nobel Prize in 1961 for his novel The Bridge on the Drina about the Bosnian city of Viśegrad under the Ottomans and the Austro-Hungarians who succeeded them.

Ádám Bodor (Transylvanian Hungarian b. 1936)

His The Sinistra Zone (1992) is a delightfully funny story of one man’s quest to find his adopted son in a Romanian bear sanctuary and military zone near the Ukrainian border and spirit him return home with him.

Mircea Cărtărescu (Romanian b. 1956)

I am on the point of finishing his novel Solenoid (2015), which is a wonderful work strongly influenced by Kafka, Borges, and Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. He has been shortlisted for the Nobel Prize and is likely to win it soon.

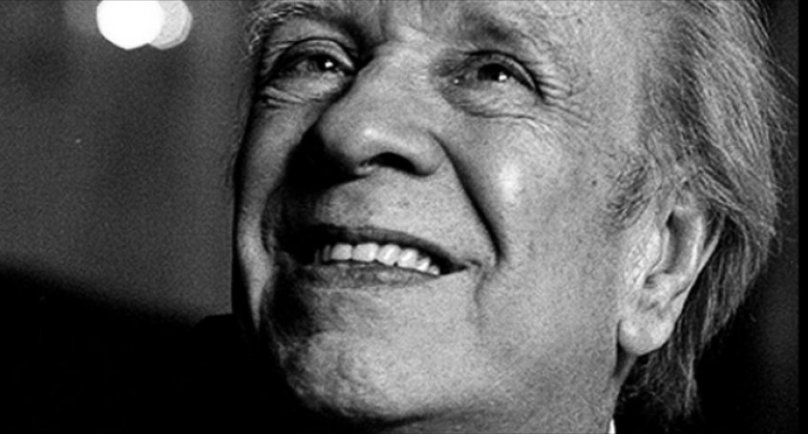

Bohumil Hrabal (Czech 1914-1997)

I have read several great novels from this Czech writer, including Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age (1964), I Served the King of England (1973), and Too Loud a Solitude (1977). His gentle humor is catching.

Franz Kafka (Czech Jew 1883-1924)

Although he wrote in German and died a hundred years ago, his work is a major influence on many of the Eastern European authors. My favorites: The Trial (1925) and his short stories.

Gyula Krúdy (Hungarian 1878-1933)

I have read most of his work that has been translated into English, but my favorites were The Crimson Coach (1913) and his journalism collected in Krúdy’s Chronicles (published in 2000).

Andrey Kurkov (Ukrainian b. 1961)

He wrote most of his works in Russian (a larger audience and more $$$), but after Putin has vowed to switch to the Ukrainian dialect. My favorites: Death and the Penguin (1996) and Grey Bees (2018).

Stanislaw Lem (Polish 1921-2006)

Yes, I know he is a sci-fi writer, but his work, especially Solaris (1961) and The Futurological Congress (1971) are of high literary quality.

Olga Tokarczuk (Polish b. 1962)

Won the 2018 Nobel Prize. So far, I’ve read only one of her novels, namely, House of Day, House of Night (1998), which is one of the best books I’ve read so far this year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.