At the end of September, I set myself a program for reading several appropriate ghoulish, ghastly, and horrifying titles in honor of my favorite holiday, Halloween. You can read about my intentions here.

Of the ten books I ended up reading last month, five were appropriate for the season:

- Ann Radcliffe: The Italian, or the Confessional of the Black Penitents

- Joyce Carol Oates: Cardiff, by the Sea

- Thomas Ligotti: The Agonizing Resurrection of Victor Frankenstein and Other Gothic Tales

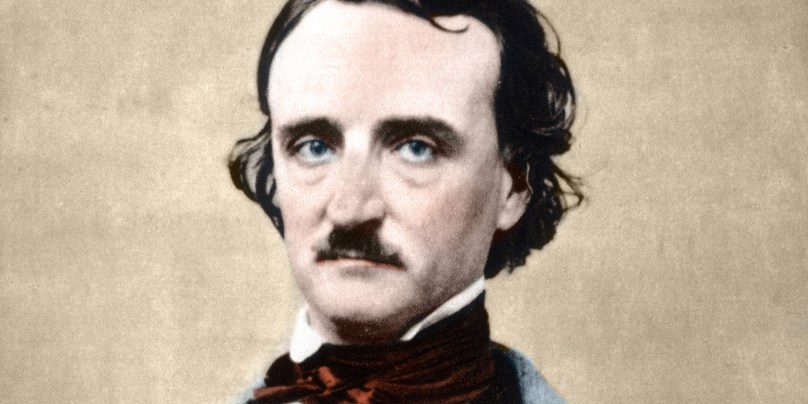

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Portable Poe

- Ray Bradbury: The Halloween Tree

They were all pretty good. Not surprisingly, I thought the Poe was best, followed by the Bradbury. That was a surprise, as it was written for the juvenile market, but I enjoyed every minute of it. The Ann Radcliffe was a hoot, as the British tended to think that nothing was spookier than Catholicism, (Maybe it was that thing about the Holy Ghost.)

I liked the Ligotti book because it was a fun way to revisit all the high points of the genre. Cardiff, by the Sea wasn’t technically a Halloween novel, except for the fact that everything Joyce Carol Oates is a bit on the spooky side.

You must be logged in to post a comment.