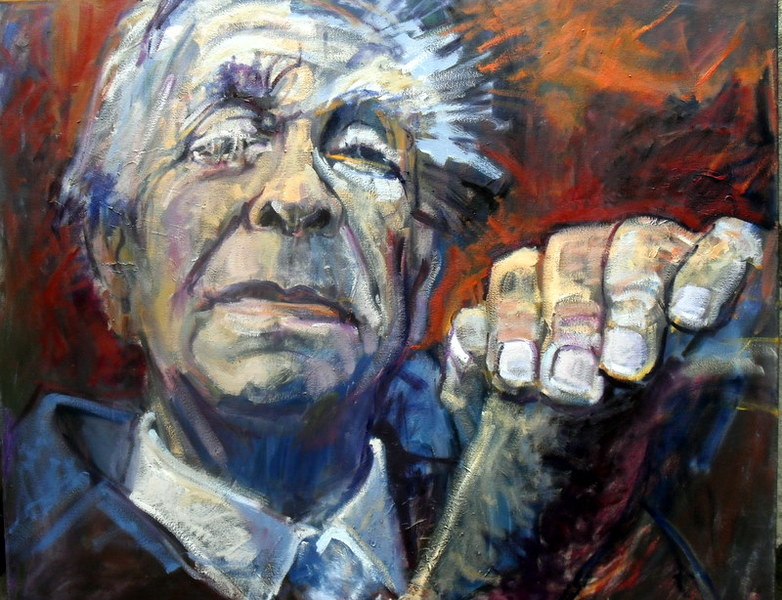

Painting of Argentinean Poet Jorge-Luis Borges (1899-1986)

This was a dream I had last night: I was taking my favorite 20th century writer, Jorge-Luis Borges on a tour of Disneyland. It wasn’t the real Disneyland: It was a dream Disneyland whose dimensions were two kilometers by two kilometers. It was interesting because it taught me something about Borges as well as something about myself.

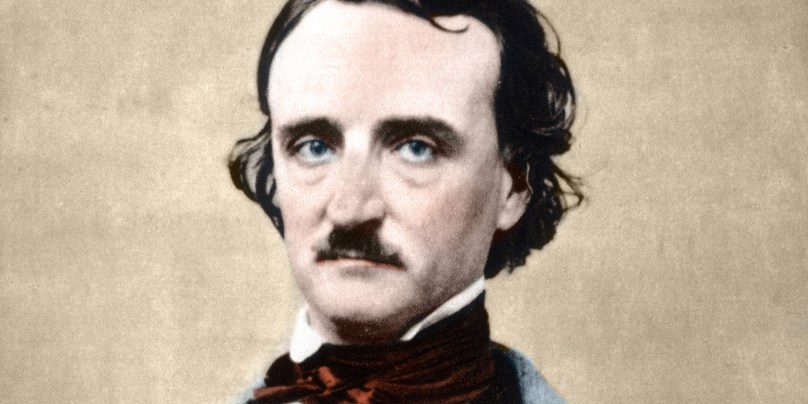

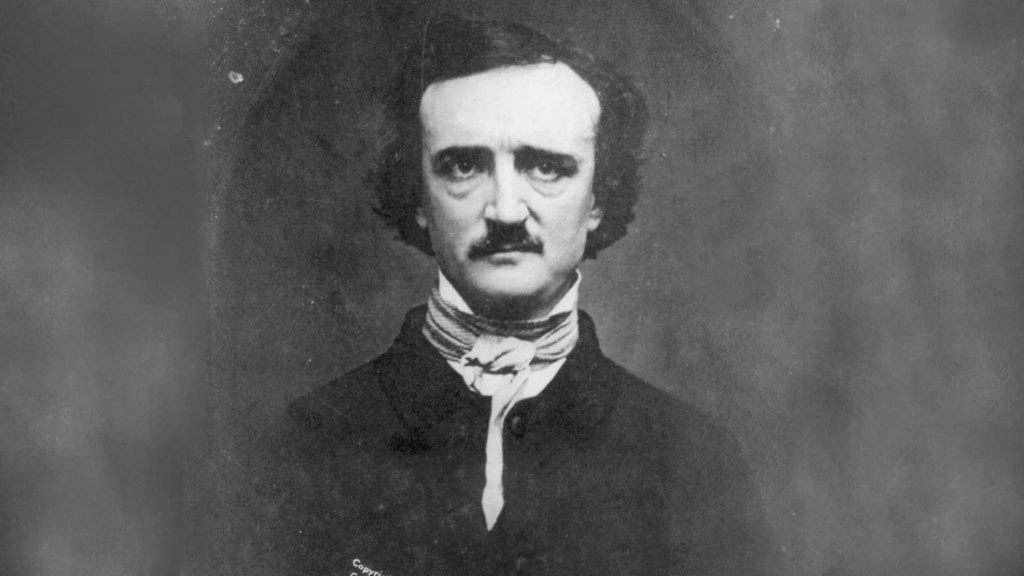

We started in a two-story pavilion dedicated to horror. I was eager to guide Borges through the different galleries, promising a special treat on the second floor, where there was a gallery dedicated to Edgar Allan Poe. At this point, Borges started to say something disparaging about Poe; but I shrugged it off and went on to the second floor, while the poet got interested in one of the ground floor galleries.

I looked forward to taking Borges to one of the restaurants in the park, but Borges said he had no interest in another buffet.

Suddenly, we cut to the railroad that circled Disneyland. It wasn’t anything like the actual railroad that goes through the park, but a more modernized train with multiple passenger cars in which we were seated on long benches facing the direction the train was going. In Disneyland, the round-the-park train seats passengers facing to the right, so that they could see the many dioramas.

At the station, I took a seat and turned to my left to see if Borges was following me. He wasn’t. Instead, a middle-aged couple sat next to me. I became agitated, as the train passed seemingly through miles of open country—a far cry from the city of Anaheim around the park. Around the halfway point, I stopped at a station and started looking for a Disney public relations rep so that he could stage a search for the lost Argentinean writer.

At this point I woke up and said to myself, “What a strange dream!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.