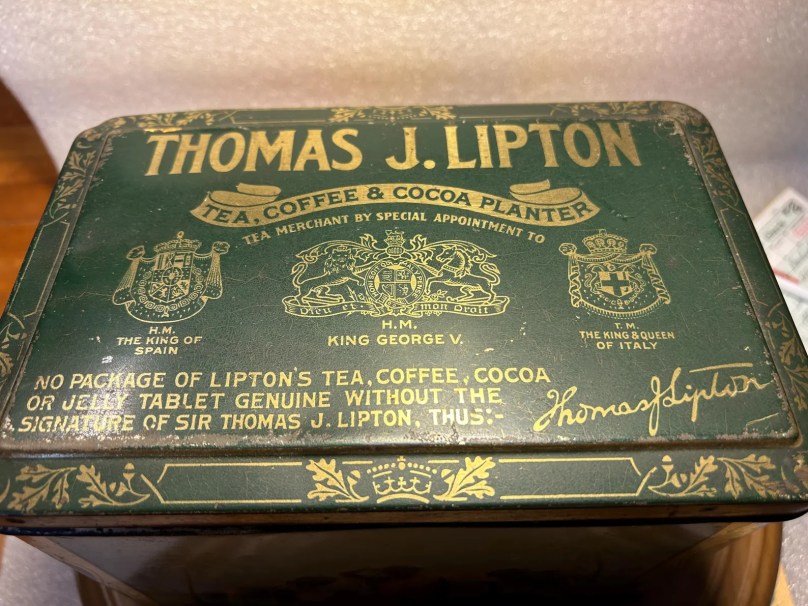

Antique Thomas J. Lipton Tea Tin

I am one of those strange people who don’t like coffee. Since early childhood, I have been addicted to tea. In my days, I have probably consumed over seventy-five pounds of tea leaves. At the present time, I begin every morning with one large cup of Ceylon, Darjeeling, or Assam tea sweetened with honey and with a squeeze of lime.

Until I read Roy Moxham’s Tea: Addiction, Exploitation, and Empire (2003), I had no idea that the history of the tea trade was so bloody. In the eighteenth century, it even figured in a war fought by the British East India Company and the Empire of China. The Chinese lost and were forced to take Indian opium in trade for their finest tea. (Read Maurice Collis’s Foreign Mud for a fascinating account of the “Opium War.”)

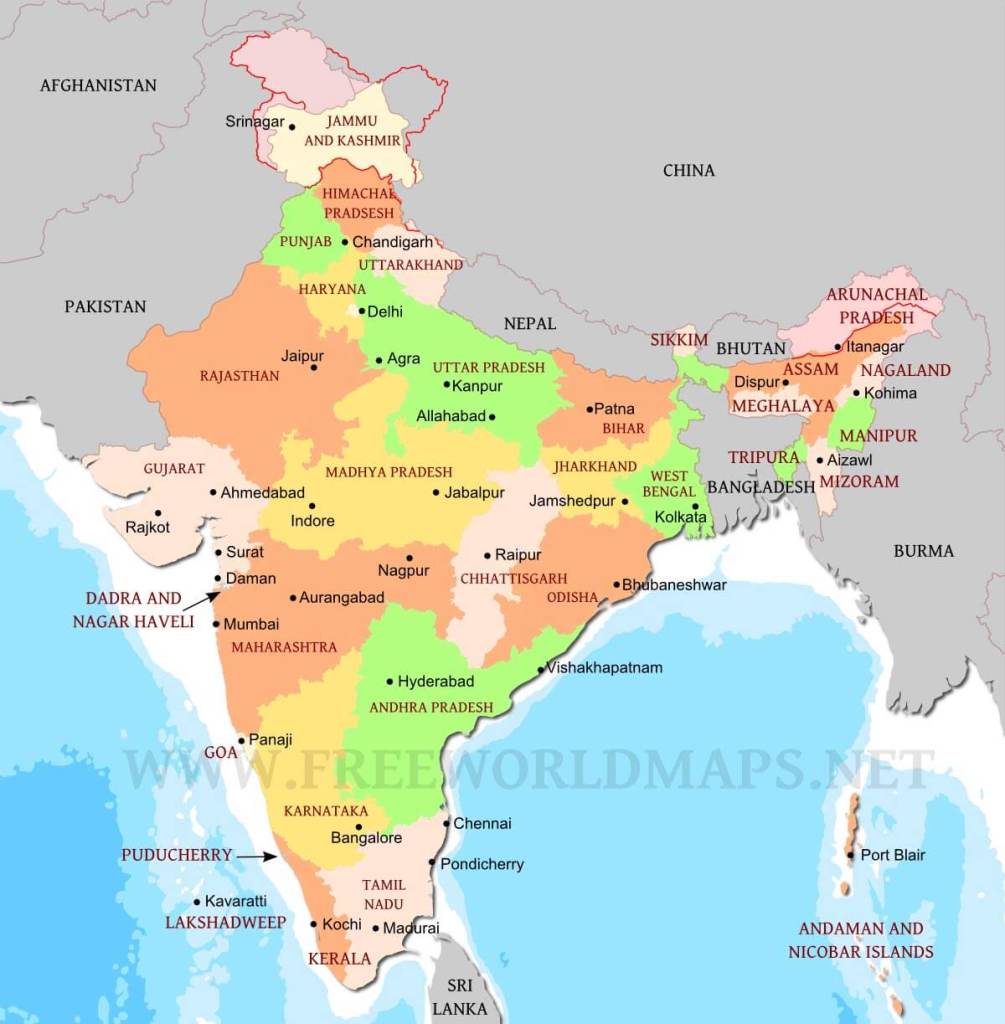

To avoid dealing with the Chinese, the British finally decided to grow their own tea. They began in the northeastern Indian state of Assam and eventually spread to other parts of the subcontinent, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Africa.

I knew that both green tea and black tea come from the same plant, the Camellia sinensis, or Chinese camellia. It is only in the way they are processed that the resulting beverage is green or black.

Fortunately, the early planters found that the tea plant was also native to Assam, and that it was not really necessary to import plants or seeds from China. It is from these plants in Assam that most tea plantings outside of China were derived.

Where the tea trade became particularly bloody was during the nineteenth century. The native populations of the tea-growing areas in India and Ceylon did not care to become indentured agricultural workers at a tea plantation. The result was that the owners of tea plantations had to import coolies from outside the area. The way these coolies were treated by the British tea growers was shameful, resulting in many thousands of deaths.

All so that I could drink a nice cup of tea in the morning!

You must be logged in to post a comment.