Cruise Ship Traveler “Discovers” Chichén Itzá

I may be revealing myself to be a grouch, but I dislike American travelers who spend the money to visit another country and don’t take the trouble to understand anything of the culture, history, or language of the countries they visit. These are the travelers who, when they ask me questions, get answered in Hungarian.

Perhaps I take my travel too seriously. For instance, when I visited Guatemala in 2019, I read nineteen books on the subject starting in February 2018. Although I frequently hired English-speaking guides at the ruins, I was at the knowledge level of a graduate student in archaeology, with a minor in history and geography.

I keep thinking of a pediatrician friend of mind who went to Europe for the first time with her fiancé and spent only a day or two in each country, just walking around and not even making an attempt to concentrate on the most interesting sights. She wound up marrying the guy and divorcing him shortly thereafter. She felt cheated, having spent so much money and seeing nothing.

It’s like visiting the Grand Canyon and spending all your time walking around the shops and restaurants in Grand Canyon Village.

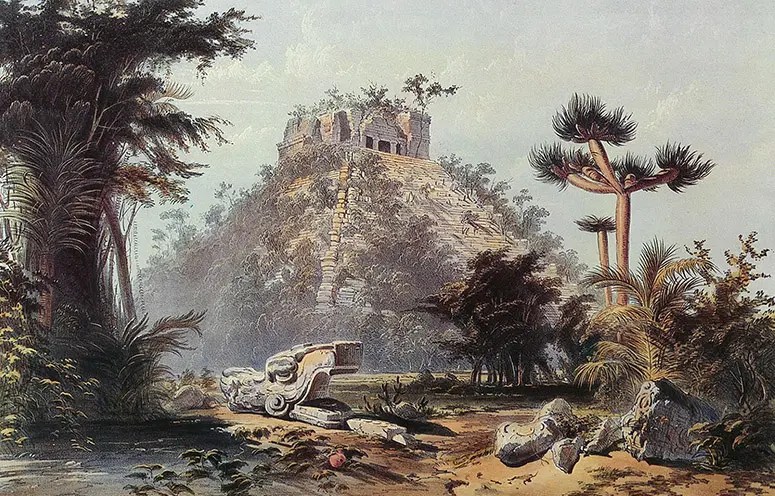

Looking at the picture above, which was taken from a current American Automobile Association (AAA) travel catalog, I wonder if the young lady standing by the Maya pyramid considered the possibility of sunstroke. Of all the thousands of people who visit Chichén Itzá every day, she was probably the only person not wearing a hat.

Looking more closely at the AAA catalog, I noticed that the ruins are an optional side trip from Cozumel, which is 2-3 hours from Chichén by ferry and bus. The grounds are extensive, as the ruins occupy several square miles. If I had to spend 4-6 hours in transport alone, I would not have much time at the ruins before having to return to my cruise ship. (I spent three days and two nights at a hotel near the ruins on my last trip there.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.