Mexican Novelist Fernanda Melchor

In this case, obscuridad is translated not as obscurity, but darkness. I toyed with the idea of calling this post “Noir Mexicana,” but I didn’t want to mix the two languages. I hope you get the general idea.

Fernanda Melchor is a very dark writer indeed. I have in the last few months read all three of her novels that have been translated into English:

- This Isn’t Miami (Aqui no es Miami)

- Hurricane Season (Temporada de huracanes)

- Paradais

All three novels are about wasted lives in the vicinity of the author’s home state of Veracruz. Although short in length, all three are crammed with violence, superstition, and fear. In the background—or sometimes in the foreground—there are the drug cartels, with scenes such as Milton in Paradais being commanded to shoot and kill a pathetic old taxi driver who is begging for his life.

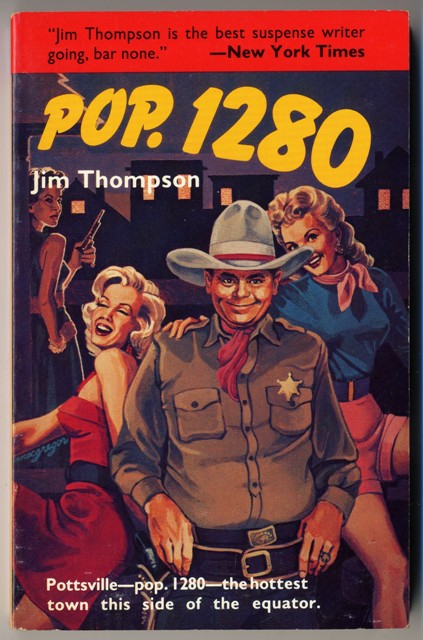

Reading Melchor is like reading Louis-Ferdinand Céline or the Jim Thompson of The Killer Inside Me. One is reminded that, in Mexico, it is easier to see the skull beneath the skin.

You must be logged in to post a comment.