Guano Island Off Peru

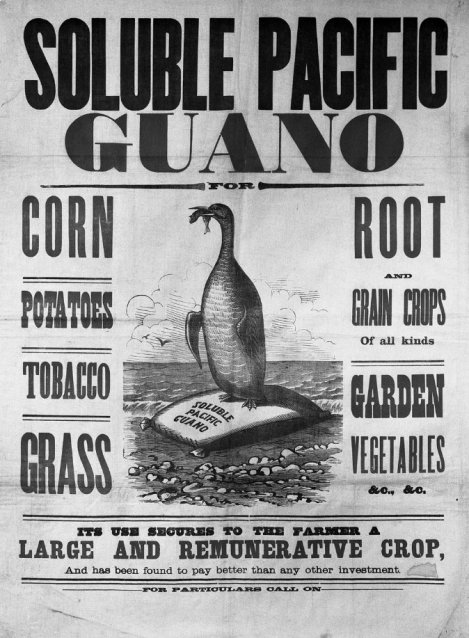

When Peru finally won its independence from Spain in the 1820s, there was no short quick route to prosperity. Much of South America’s economy was primarily agricultural, based on large haciendas, many of which had just changed hands from Spanish loyalists to officers of the revolution. It took about twenty years before Peru discovered that its primary source of wealth was actually bird sh*t. There were a number of islands off the coast of the Atacama Desert in the south that were covered to a depth of several meters with a centuries’ long accumulation of guano. Europe, which was trying to recover from the ravages of the Napoleonic Wars, needed the fertilizer to insure rich crops.

Mining the guano was no picnic. Peru imported thousands of laborers from China to dig up and bag the guano for shipment to a customer base that was willing to pay top dollar for the … stuff. Native Peruvians did not breathing in the noxious particles, so it was mostly immigrants who worked the islands. For about thirty years, Peru was sh*tting pretty, until it hit the fan. (Had enough of the puns yet?)

After much of the guano was shipped overseas, it was discovered that the Atacama Desert was rich in nitrate fertilizers, which were a good substitute for the organic stuff. At this point, the main actors in the business were Peru, Bolivia (which then had a seacoast), and Chile. Bolivia arbitrarily raised the taxes on mining nitrates. As many of the companies supervising the mines and transporting the fertilizer were Chilean, they demanded tax relief. Bolivia refused, and Peru backed Bolivia.

What Kind of Bird Izzat?

In 1879 began the War of the Pacific, with Chile arrayed against both Peru and Bolivia. As Chile had better military leadership and weaponry, it won handily after a number of bloody sea and land battles. The upshot was that Bolivia lost its access to the sea (though they still have admirals for some reason), and Peru lost its State of Tarapacá, including Tacna, Arica, Iquique, and Pisagua. (Eventually Tacna was ceded back to Peru some years later.)

In the end, the British took over the nitrate mining industry, with most of its associated profits. Bolivia suffered the most, as it lost all access to the Atacama Desert. Peru was outraged at having been occupied by Chile, though it fought a fairly successful guerrilla insurgency. Nonetheless, it had suffered a humiliating defeat with repercussions lasting to the present time.

As to the profits from fertilizer mining, they dwindled rapidly; and Peru went from being a wealthy country to being an economic basket case.

For more information, click here for a good illustrated review of the 19th century guano mining industry.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.