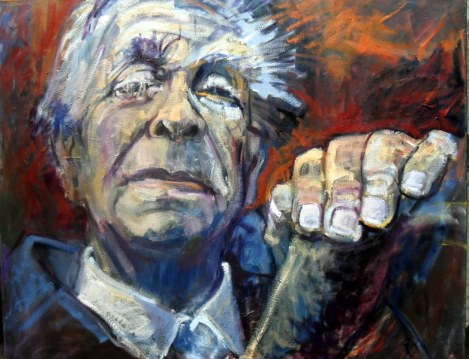

Argentinian Author and Poet Jorge Luis Borges

In 1935, Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story entitled “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim.” In it, he writes of a man who, after a religious riot between Hindus and Muslims, “becomes aware of a brief and sudden change in that world of ruthlessness—a certain tenderness, a moment of happiness, a forgiving silence in one of his loathsome companions.” He concludes that “somewhere on the face of the earth is a man from whom this light has emanated; somewhere on the face of the earth there exists a man who is equal to this light.”

For me, the source of that light—at least in the world of 20th Century literature—is Jorge Luis Borges himself. I have read all his works that have been translated into English, and even the many interviews he conducted toward the end of his life. I am now on the lookout for ever more obscure works … and I think I have found a good candidate.

The book is by Argentinian author and filmmaker Edgardo Cozarinsky, and its title is Borges In/And/On Film (New York: Lumen Books, 1988). Its three parts consist of:

- Reviews of films written by Borges before his blindness became total in the 1950s.

- The influence of Borges on film critics and filmmakers (mostly French).

- A survey of films based on Borges’s stories or scripts.

The parts become decreasingly interesting from one part to the next. He had a curious liking for the films of Josef von Sternberg—before that director had discovered Marlene Dietrich. Afterwards he regards him as “a devotee of the inexorable Muse of Bric-à-Brac.” Reviewing an Argentinian film, Borges writes it “is unquestionably one of the best Argentine films I have seen, which is to say, one of the worst films in the world.”

Of Citizen Kane, he writes that it “suffers from gigantism, from pedantry, from tediousness. It is not intelligent, it is a work of genius—in the most nocturnal and Germanic sense of that bad word.”

Of Victor Fleming’s version of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Borges complains that he “avoids all surprise and mystery; in the early scenes of the film, Spencer Tracy fearlessly drinks the versatile potion and transforms himself into Spencer Tracy, with a different wig and Negroid features.”

Although Borges did no write many film reviews, many of his observations are interesting. He also has made one notable howler: Recalling Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), he writes:

Thus, in one of the noblest Soviet films, a battleship bombards the overloaded port of Odessa at close range, with no casualties except for some marble lions. The markmanship is harmless because it comes from a virtuous, maximalist battleship.

It is not the Potemkin that bombards Odessa, but the Czarist Black Sea Fleet, whose shooting results in a massacre.

The above painting is the work of Beti Alonso.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.