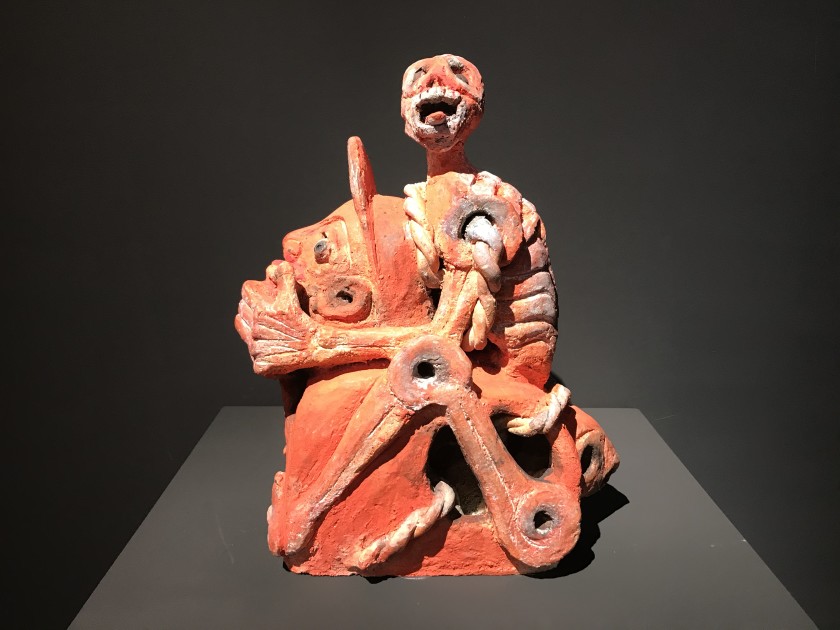

Mixtec Ruins at Mitla, State of Oaxaca, Mexico

It was January 1980. My brother and I were traveling in an arc across southern Mexico along a route taken by Graham Greene in the 1930s, when he was doing his research for The Power and the Glory, which he described in his travel book The Lawless Roads.

Dan and I flew to Mexico City, transferring there to a flight to Villahermosa, which was the least hermosa (beautiful) city either of us had seen in all of Mexico. From there, we went to Palenque, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Oaxaca, and back to Mexico City via all-night bus.

While we were in Oaxaca, we took a side trip to see the Mixtec ruins at Mitla, which consisted of numerous geometric motifs such as are shown in the above photo. Seeing ruins in the desert makes one hungry and thirsty, so we repaired to a little restaurant within shouting distance of the ruins.

We were the only customers in the place. After a few minutes, a little girl raced out of the kitchen and stopped dead in her tracks, seeing two large and hairy gringos seated at a table. She did a quick U-turn and ran back to the kitchen shouting ¡Mamacíta! Within a couple of minutes, her mother appeared at our table with a notepad asking in Spanish what we wanted. Dan and I both ordered chicken enchiladas, rice, and beans.

There followed a long delay of several minutes which was punctuated with what Dan and I recognized as the death squawk of a chicken whose neck was being wrung. (Our great grandmother, old Hungarian farm woman that she was, liked to buy live poultry and butcher them and pluck their feathers herself.)

In time, about thirty minutes in all, our lunches were served. The chicken which had given its all for us turned out to be old and tough, with a decidedly stringy texture. It had been old, but by God it was fresh! We did our level best to eat as much as we could before thanking the proprietor and her daughter and making our way to the bus terminal.

That was a fun trip which gave us dozens of funny stories to remember for the long years to come.

You must be logged in to post a comment.