Tiwanaku: Gate of the Sun

I must think I’m going to live forever.Trapped in my apartment during the quarantine, I am thinking more and more about returning to Peru and including the altiplano of Bolivia. Here I am at age 76, thinking of a strenuous trip at high altitude to one of the most fascinating (albeit difficult) places on Earth.

In 2014, I spent some time on the western shore of Lake Titicaca, on the Peru side. I even took a tour on a launch to Isla Taquile and one of the Uros Isles, but as the boat left the dock, I discovered that I was beginning to suffer the effects of food poisoning. The former afternoon at Sillustani, I ate something in a farmer’s house that violently disagreed with me. What is more, I was hours away from a toilet. Under the circumstances, I was not able to appreciate the beauties of Lake Titicaca, and in fact I took no pictures that day.

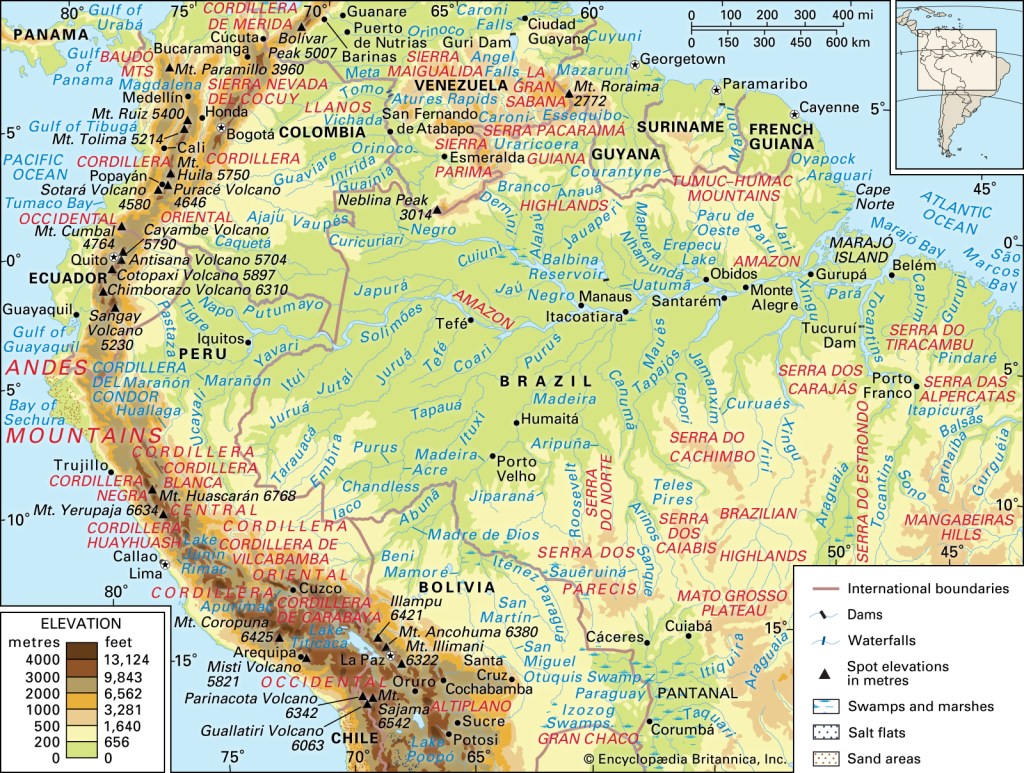

Map of Lake Titicaca, Showing the Location of Tiwanaku at Lower Right

Just as I returned to Tierra Del Fuego after breaking my shoulder there in 2006, I plan on returning to the Peruvian side of the lake, and adding some parts of Bolivia to the mix. I find myself suddenly interested in the Aymara-speaking peoples of the Andes.

A funny thing happened to me in Puno during my last visit. It was a bitterly cold morning, as it frequently is at that altitude (12,000 feet or 3,700 meters). I had neglected to bring a scarf with me, and I badly needed one. Enter a poor Aymara woman laden down with hand-knitted handicrafts. I walked up to her and brought a beautiful scarf at a reasonable price. Apparently, I made that woman’s day. She broke into a big smile and was almost prepared to welcome me into her family.

Over a thousand years ago, there was an Aymara empire centered at Tiwanaku in modern-day Bolivia. It lasted until AD 1100 when a massive and persistent drought led to a drop in the level of Lake Titicaca, leaving the Aymara fields high and dry. Hundreds of years later, the Inca took over; but their empire was short-lived once the Spanish conquistadores began to move in.

Walls of the Kalasaya Complex at Tiwanaku

Since the eco-catastrophe that destroyed the Aymara empire a thousand years ago, the Aymara have become a scattered people indulging in subsistence agriculture and the herding of llamas and alpacas.

You must be logged in to post a comment.