A City Surrounded by Mountains

The other night I dreamed of Bolivia. I was in La Paz, one of the country’s two capitals—the other is Sucré in the South. I was trying to navigate between two locations within the city, but all I had was a two-dimensional street map that didn’t give me any idea whether I had to go uphill or downhill. The Lonely Planet guide to Bolivia lists the altitude of La Paz at 12,007 feet (3,660 meters), but isn’t that just an average? Even higher than La Paz is the erstwhile suburb of El Alto, which is, at 13, 620 feet, not only the highest major metropolis in the world with a million people, most of them Aymara, but also is home to the La Paz’s international airport,the world’s highest.

I am obsessing about La Paz: It is a city that pops up in my dreams because it is set in a huge bowl under several conical volcanoes, the most spectacular of which is Illimani at 16,350 feet. I keep thinking of traveling up and down the city by taxi and on foot, gasping all the while because of the high altitude.

Currently, I am thinking of starting my vacation in Lima and traveling through southern Peru to Lake Titicaca and then on to La Paz. From there, I plan to fly “open jaws” back to Los Angeles. That saves me time and money from having to deadhead back to Lima.

The big question is my susceptibility to Soroche, or altitude sickness. If, upon arriving in Cusco, I appear to have the beginnings of either HAPE (high altitude pulmonary edema) or HACE (high altitude cerebral edema), I will turn around and return to Arequipa, going on to Tacna (in Peru) and Arica (in Chile), possibly as far as Antofagasta. In that case, I would deadhead back to Lima and fly home from there.

So if that alternate scenario takes place, I would have to have a flight from La Paz to Los Angeles that I can cancel if necessary. Is that possible? It remains to be seen.

Addendum: These two quotes from Christopher Isherwood’s South American diary, The Condor and the Cows, add an eyewitness’s observations to the city :

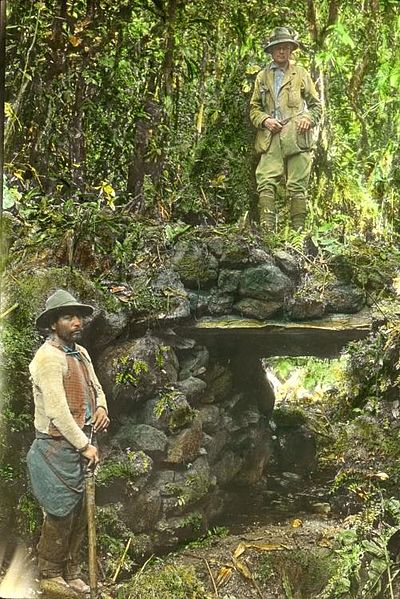

Sixty miles from the lake [Titicaca] the plain suddenly ends. You look over its edge into a deep horse-shoe valley and there is La Paz, fourteen hundred feet below. The view makes you gasp, for it is backed by the enormous snow-peak of Illimani, which fills the sky to the south. Illimani is rather higher than Mount Pelion would be if it were piled not on Ossa but upon Mont Blanc.

Believe it or not, I actually had the following scene in my dream:

Many of the side streets are so steep that you could scarcely hold your footing on the worn pavement. The Paceños have learned to slither down it in long strides, like skaters. What with the altitude, the gradients, the scarcity of elevators and the shortage of taxis, you spend most of the day painfully out of breath, and envy the Indians, whose enormous lungs enable them to trot uphill without the least sign of strain.

You must be logged in to post a comment.