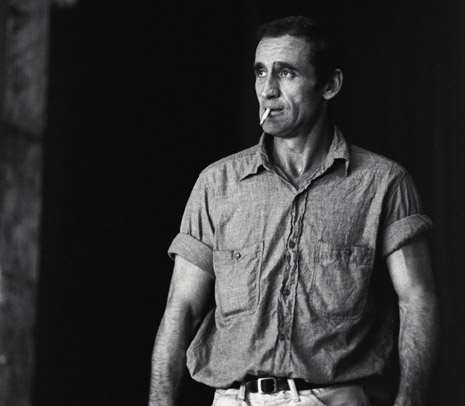

Philosopher Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997)

We don’t read philosophers much any more. That’s a pity. Even though their works can be difficult, there is a payoff. I am thinking, for instance, of the late Isaiah Berlin, who died in 1997. Years from now, people will be referring to him as the greatest 20th Century thinker about human liberty.

Twenty years ago, on November 25, 1994, he accepted an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from the University of Toronto. On that occasion, he pleaded with people not to give way to a passionate idealism that violates individual freedoms:

I am afraid I have no dramatic answer to offer: only that if these ultimate human values by which we live are to be pursued, then compromises, trade-offs, arrangements have to be made if the worst is not to happen. So much liberty for so much equality, so much individual self-expression for so much security, so much justice for so much compassion. My point is that some values clash: the ends pursued by human beings are all generated by our common nature, but their pursuit has to be to some degree controlled—liberty and the pursuit of happiness, I repeat, may not be fully compatible with each other, nor are liberty, equality, and fraternity.

That Business of Making Omelettes

That is one of the reasons I so distrust conservative ideologues such as Ted Cruz and Paul Ryan: For the sake of their ideological purity, they are willing to deprive us, if necessary, of our liberties. (By the way, I feel the same about liberal ideologues, even though they have not been much in evidence lately.) Berlin goes on:

We must weigh and measure, bargain, compromise, and prevent the crushing of one form of life by its rivals. I know only too well that this is not a flag under which idealistic and enthusiastic young men and women may wish to march—it seems too tame, too reasonable, too bourgeois, it does not engage the generous emotions. But you must believe me, one cannot have everything one wants—not only in practice, but even in theory. The denial of this, the search for a single, overarching ideal because it is the one and only true one for humanity, invariably leads to coercion. And then to destruction, blood—eggs are broken, but the omelette is not in sight, there is only an infinite number of eggs, human lives, ready for the breaking. And in the end the passionate idealists forget the omelette, and just go on breaking eggs.

For Nazism in Germany, the original goal was to unite the rich and poor in a common national project (“Volksgemeinschaft” or people’s community) and “promoted the subordination of individuals and groups to the needs of the nation, state and leader” (Wikipedia) Of course, it was not for all. Jews, Communists, Gypsies, Slavs, and other non-Aryans were rounded up and eliminated.

In Russia, everything was subordinated to the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, which never quite happened.

As for the United States in the 21st Century, I conclude with Yeats in his poem “The Second Coming”:

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Does that make me wishy-washy? To some, perhaps, but I would rather lack all conviction than be full of a passionate intensity that deprives anybody of the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

If you’d like to see the complete text of Berlin’s address, you will find it on Page 37 of the October 23, 2014 issue of The New York Review of Books under the title “A Message to the 21st Century.”

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.