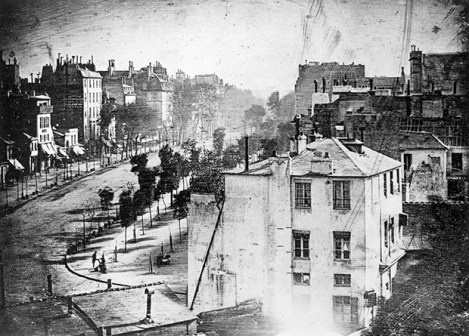

Political Cartoon Regarding the Chaco War

This post is about three wars fought in South America between1864 and 1935—wars that most people in the United States have never heard of. Yet withal they were extremely bloody, involved transfers of large amounts of territory between the combatants, and set some of the participants back for decades.

The War of the Triple Alliance

Here’s one that’s difficult to even imagine, considering the unevenness of the sides. Arrayed on one side was Paraguay under dictator Francisco Solano López, one of the more imbecilic caudillos in South America’s bloody history. Arrayed against it was Brazil. But wait, there’s more. Argentina and Uruguay jumped in on the side of Brazil. This is also referred to as the Paraguayan War. Before López and 1.2 million Paraguayans, or 90% of the pre-war population, was killed. You can read about it in John Gimlette’s wonderful book about Paraguay called At the Tomb of the Inflatable Pig. After this war, Paraguay pretty much disappeared from the world scene—until it was time for the next war it fought.

The War of the Pacific

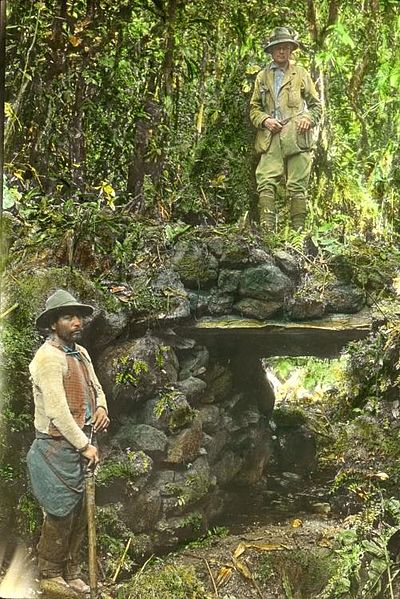

We move ahead to period 1879-1884. Bolivia actually had a seacoast with seaports back then, and its lands in the Atacama Desert were a rich source of nitrates. These were mined by a Chilean company called the Antofagasta Nitrate & Railway Company. The adjacent parts of Peru around Tacna and Arica were also being mined for nitre, which was at the time the number one export of Pacific South America. But then Hilarion Daza, the idiot caudillo of Bolivia, decided to levy a tax against the Chileans, and the nitre hit the fan. Chile invaded the Bolivian. Unfortunately for Peru, it had a mutual defense alliance with Bolivia, so it joined the fray.

Although the armies of Peru and Bolivia greatly outnumbered the Chileans, the Chileans were better officered. As William F. Sater wrote in his excellent Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884:

Peruvian intellectual Ricardo Palma said of the officer corps that “for every ten punctilious and worthy officers, you have ninety rogues, for whom duty and motherland are empty words. To form an army, you have to shoot at least half the military.”

In addition, there was one commissioned officer and one non-commissioned officer for every three privates. That’s not a terribly good ratio.

Anyhow, Bolivia and Peru lost the war and huge amounts of territory, and Bolivia became a landlocked country.

The Chaco War

This one is between the only two landlocked countries in South America, Bolivia and Paraguay—two losers if there ever were any. It was fought over the Gran Chaco, an area that was thought to harbor vast oil reserves. Typically, Royal Dutch Shell supported Paraguay; and Standard Oil backed Bolivia. This war is also called La Guerra de la Sed, or “The War of Thirst,” because so many of the combatants died of thirst fighting among the cacti of the arid region.

Between 1932 and 1935, the Chaco War led to lots of casualties, and a gain for Paraguay, which surprisingly won the war:

By the time a ceasefire was negotiated for noon June 10, 1935, Paraguay controlled most of the region. In the last half-hour there was a senseless shootout between the armies. This was recognized in a 1938 truce, signed in Buenos Aires in Argentina and approved in a referendum in Paraguay, by which Paraguay was awarded three-quarters of the Chaco Boreal, 20,000 square miles (52,000 sq km). Two Paraguayans and three Bolivians died for every square mile. Bolivia did get the remaining territory that bordered Paraguay’s River, Puerto Busch.

Over the succeeding 77 years, no commercial amounts of oil or gas were discovered in the portion of the Chaco awarded to Paraguay, until 26 November 2012, when Paraguayan President Federico Franco announced the discovery of oil reserves in the area of the Pirity river…. The President claimed that “in the name of the 30,000 Paraguayans who died in the war” the Chaco will become the richest oil-bearing region in South America. Oil and gas resources extend also from the Villa Montes area and the portion of the Chaco awarded to Bolivia northward along the foothills of the Andes. Today these fields give Bolivia the second largest resources of natural gas in South America after Venezuela. (Wikipedia)

Again, Gimlette’s At the Tomb of the Inflatable Pig is a good source of the only war that Paraguay could be said to have won, though it was only a booby prize for decades.

The cartoon above is taken from Poliical Cartoon Gallery by Derso and Kelen, which is well worth a look.

You must be logged in to post a comment.