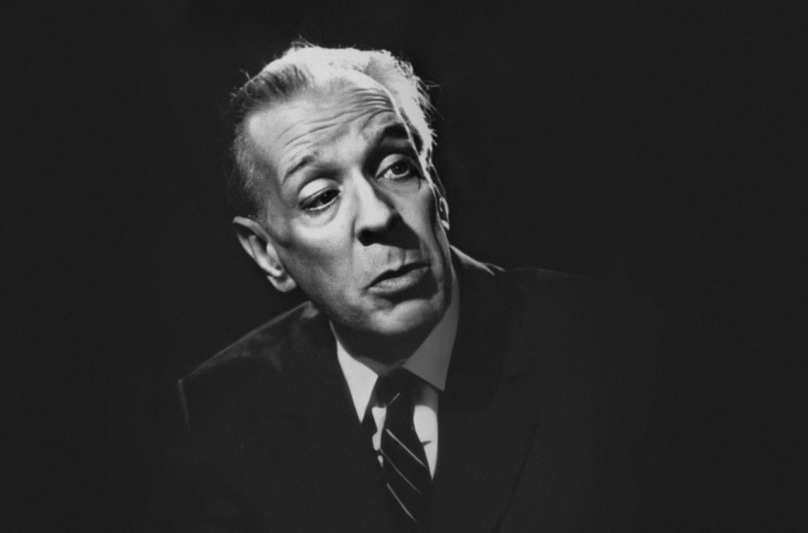

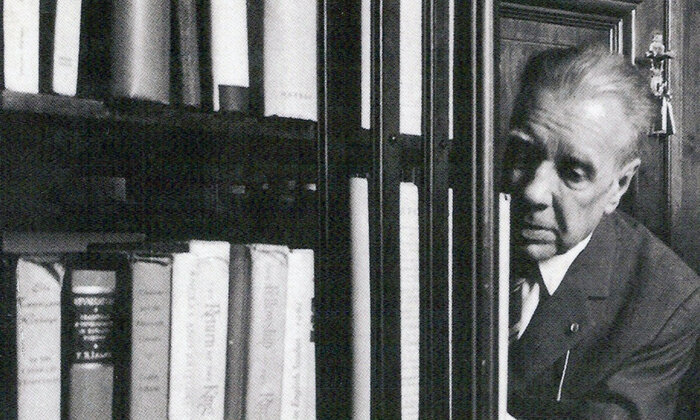

Argentinean Poet Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986)

Here is another great poem by Jorge Luis Borges, a poet who has had perhaps a greater influence on my life than any other. Among other things, my thirst for knowledge about him has led me to Buenos Aires three times in the last twenty years.

Limits

Of these streets that deepen the sunset,

There must be one (but which) that I’ve walked

Already one last time, indifferently

And without knowing it, submitting

To One who sets up omnipotent laws

And a secret and a rigid measure

For the shadows, the dreams, and forms

That work the warp and weft of this life.

If all things have a limit and a value

A last time nothing more and oblivion

Who can say to whom in this house

Unknowingly, we have said goodbye?

Already through the grey glass night ebbs

And among the stack of books that throws

A broken shadow on the unlit table,

There must be one I will never read.

In the South there’s more than one worn gate

With its masonry urns and prickly pear

Where my entrance is forbidden

As it were within a lithograph.

Forever there’s a door you have closed,

And a mirror that waits for you in vain;

The crossroad seems wide open to you

And there a four-faced Janus watches.

There is, amongst your memories, one

That has now been lost irreparably;

You’ll not be seen to visit that well

Under white sun or yellow moon.

Your voice cannot recapture what the Persian

Sang in his tongue of birds and roses,

When at sunset, as the light disperses,

You long to speak imperishable things.

And the incessant Rhone and the lake,

All that yesterday on which today I lean?

They will be as lost as that Carthage

The Romans erased with fire and salt.

At dawn I seem to hear a turbulent

Murmur of multitudes who slip away;

All who have loved me and forgotten;

Space, time and Borges now leaving me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.